Netflix reality shows Love is Blind and The Circle felt like ridiculous, entertaining guilty pleasures a few months ago. Now, they’re handbooks for uncharted territory.

Featured image design by Elisabeth Oster. Photo courtesy of Netflix.

Tropical breezes and endless luxuries only Netflix money can buy surround the six couples on the recent reality dating show Love is Blind; the couples are honeymooning in sun-drenched Mexico—only days after seeing each other for the first time. And yet, there’s a longing. Not one of lust or increased interaction with individuals who they’re set to marry in a month’s time. Instead, multiple couples look straight into the camera, sighing wistfully as they long for the complete opposite: to go back to the futuristic pods where their “romance” was formed. While in paradise and with full access to the individual they supposedly fell for, they long instead for the separation of four walls with only the other individual’s voice to keep them company.

This desire and preference over face-to-face connections is so intense for some lovebirds that at one point, days before the wedding, superficial pairing Jessica and Mark devise a date where they enjoy their meals in separate rooms of their apartment. In any other circumstance, this would rank in the worst and weirdest date anyone could possibly experience, but for Jessica, she gushes that the pod-like set up is her “comfort” and “brings down the walls.”

On paper, the concept sounds rather surface level and unfathomable when it comes to the normal processes and interaction that is necessary for any type of relationship. The creators behind Love is Blind are fixated on the idea of testing if “love is really blind” by conducting a week of dates in the pod structures, resulting in five engagements. Those who were gutsy enough to propose to someone they knew for a week with reckless abandonment, have a honeymoon after getting to see each other for the first time.

After a brief stint living with each other back home in Atlanta, the saga for the five remaining couples ends with a harmonious marriage or a train wreck of a wedding perfectly tailored for reality television. The elusive hosts, Nick and Vanessa Lahey, proudly tote the show as an “experiment” and seem to suggest that they’ve successfully proved that “love is blind” (whatever that really means).

This isn’t Netflix’s first foray into the burgeoning subgenre of virtual reality television—months earlier, The Circle beckoned to Netflix subscribers as a new competition show. The twist, however, was that each contestant was holed up in their own apartment, separate from each other by mere rooms complete with food and supply delivery; best described as a real-life simulation of the functionality of social media, players had profiles with photos and statuses to update as well as private group chats filled with carefully crafted messages—almost identical to a social media platform like Instagram.

Through a series of small challenges, group chats, photo profiles, and a heavy dose of deceiving (some contestants used other’s photos, breathing new meaning into the word “catfish”), the contestants voted for one of them to become the winner, or the top “influencer,” as the show puts it. The “influencer” was able to use their supposed appearance and likeability through text communication while influencing players to doubt how real others were being behind the screen. With this premise around likeability in the digital world, The Circle not only highlighted how different people are able to come across in a virtual setting—both unintentionally and with malintent— but also how surface-level relationships can be when dependent on social media profiles and text communication.

Both Netflix productions became ridiculously popular when they released. The public laughed at the ridiculousness of couples so obviously wrong for each other, blaming the lack of attraction on the fact that they were no longer in the comfort of their separate pods or contestants pacing around their isolated apartments, speaking to their TV system. But in a cruel twist of irony, mere months after these shows revealed a trend towards virtual conversation, the whole world began living it.

The actions of the individuals that inhabited these shows didn’t feel so ridiculous anymore, but a real possibility. A concept that existed firmly as a depressing possibility of the extremes of online communication mere months prior became a reality forcibly imposed on the population as a whole. There’s now a distinct comfort to see contestants on The Circle make increasingly offbeat choices to pass time the longer they’re contained in their manufactured apartments. From solitary card games, Rubik’s Cubes, and puzzles—the players paved the way for promoting quarantine activities.

This article, originally meant to be written closer to the initial fervor surrounding Love is Blind and the depressing implications it provided to society, unexpectedly grew in relevancy as the initial deadline passed—something this writer never anticipated. As the days of social distancing pass and blur together, many are desperately grasping for human interaction through social platforms—virtual happy hours, movie nights, and birthday parties populate the virtual space.

But perhaps the most interesting development is a crop of virtual first dates. Across the world, eligible but decidedly stranded singles are using Venmo and delivery apps to emulate the awkward energy of dating via apps. In a new world of meeting romantic prospects among the comforts of home, the awkwardness of eating in front of someone you’ve just met and the festering question of who pays is bafflingly preserved. Such an action seemed futuristic when The Circle players sat down to indulgent martinis and hors d’oeuvres, facing a screen to talk to a competitor on the other side. While the world pauses, love lives are prospering out of pure boredom, aided by the powerful trappings of social media with shows Love is Blind and The Circle as an unconventional social handbook—let’s call it Unconventional Relations for Unconventional Times.

Just as fast as the trajectory of the current situation shifts and veers to unknown futures, so did the thesis of the pitched article. It was supposed to be a tale of the importance of real, raw connection more than ever during the digital age. It was supposed to discuss the dangerous implications that highly-consumed media like these Netflix shows has on how we choose to meet others. It became a look at how the same shows provide comfort and a how-to guide in the thick of quarantined existence: the new Marie Kondo of how we structure our lives. And although I’ll forever argue that nothing beats taking in another person’s entire essence—each expression, each hand gesture, each comfortable silence—it’s become more important to hastily figure out how to maintain established relations unequivocally online.

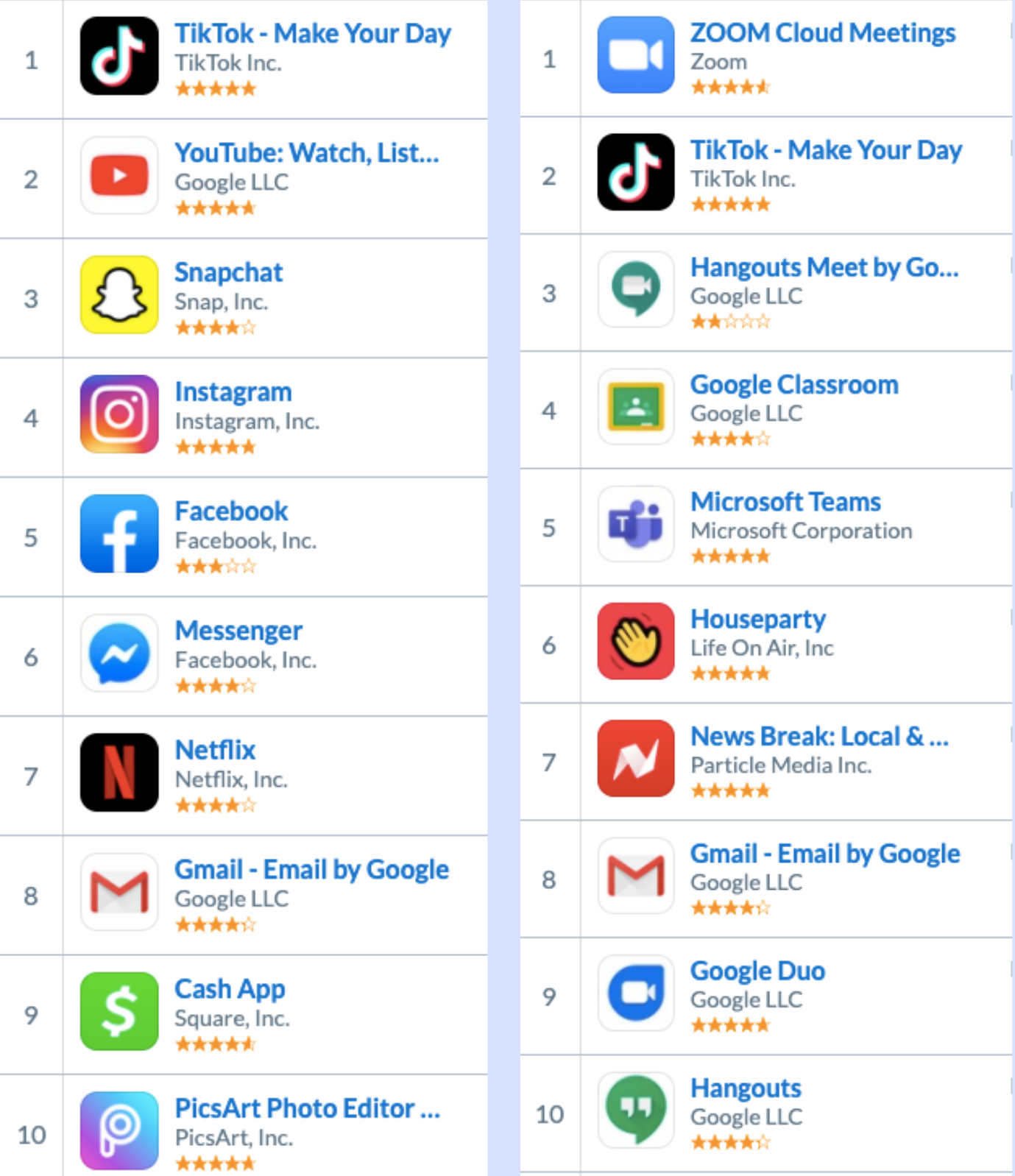

Even App Store statistics echo this changing landscape. At the beginning of March, the top 10 most downloaded free apps consisted of traditional social media such as YouTube, Snapchat, Instagram, and Facebook. In a month’s time and 80,000 American coronavirus cases later, the top 10 is devoid of familiar social networking; instead, the charts welcome a different type of networking in the form of Google Hangouts, Microsoft Team, and Houseparty. Zoom has overtaken TikTok’s months-long reign as the number one most downloaded app. The world is changing, shifting, and evolving.

In some ways, this shift is promising as it provides evidence that real human conversation is valued over the more constrictive style of communication seen in Love is Blind and The Circle with voice-only methods and dinner dates via text, as well as in more superficial forms like social media. In other respects, a hurried push towards completely virtual communication will inevitably become a more normalized standard. As of now, virtual watch parties and game nights are done out of necessity, as a creature of comfort during theatrical times.

As with anything, good can come out of massive and dire situations—staged, pristine photos and manufactured comments of adoration began disappearing on social media the moment the world became housebound. Space is being made on such platforms for authentic communication, and more glimpses of authentic human life appear out of unified boredom and a craving for distraction. It feels fresh and novel currently to see people decide to post unflattering photos or find creative solutions for normalcy—the exact opposite of what The Circle set out to show by exposing the deception and inauthenticity of social media. The actions of these people inviting authenticity into their virtual life bring a little hope to a usually negative technological outlook.

Further down the road, this style may become the norm for how we treat social media, viewing it as a vessel for distraction and connection, rather than a façade for the onlooker. And maybe, just maybe that wouldn’t be so bad. Up until now, the virtual world has been firmly superficial; learning how to utilize the virtual space for our real lives is an inevitable next step to grow past its function as a glossy accompaniment to a real self. It’s just coming sooner than anyone ever expected.

One could argue whether Love is Blind indisputably shows that pure love rests solely on personality or that The Circle really emulates the dangers of social media; either way, it definitely provides an argument about where communication is inevitably going as our physical body separates from our interacting souls. On March 24, Netflix announced that both Love is Blind and The Circle were renewed for two additional seasons, almost insinuating to its audience to buckle up and get used to a new reality.